By D. Kevin McNeir

Dred Scott, born in Southampton, Virginia in 1799, was a slave living in St. Louis, Missouri in 1846 with his wife and their two children, when he, like so many others before and after him, set his mind on securing their freedom. However, instead of hitching a ride on the Underground Railroad, he chose a less common means – the U.S. court system.

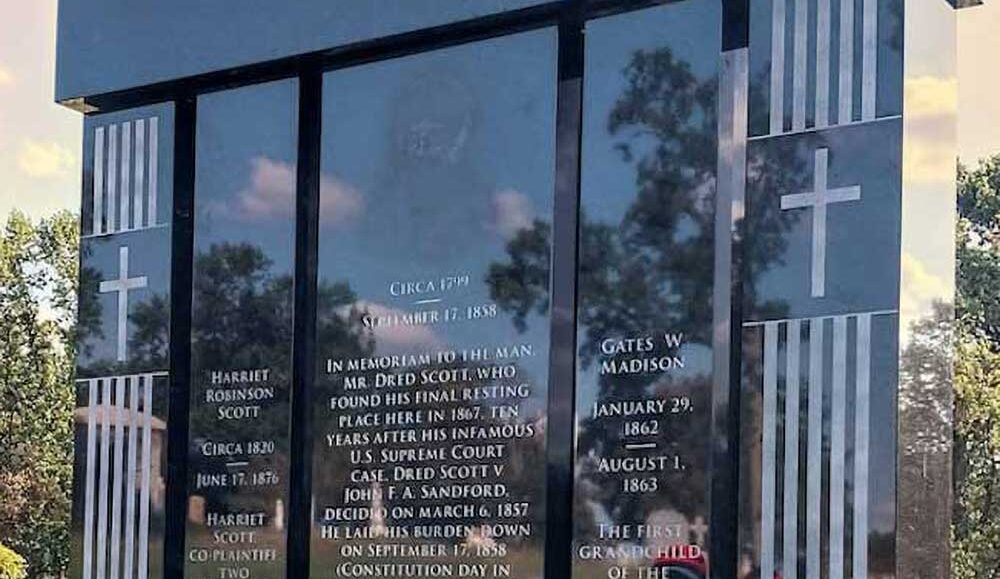

Now, 165 years after the U.S. Supreme Court case was decided and which bears his name, Scott’s gravesite at Calvary Cemetery & Mausoleum, in St. Louis, that went unmarked for nearly 100 years after his death, serves as a memorial to his life and legacy.

The dedication of the monument took place on October 10, led by Scott’s great-granddaughter, Lynne M. Jackson, founder of the Dred Scott Heritage Foundation.

As a child she visited the gravesite with her parents when only a small marble tablet bore the name of her ancestor. Now, that tablet has been replaced by a large slab several feet high inscribed with essential information about Dred Scott’s life.

“I began a fundraising drive after seeing how many people wanted to visit his grave,” she said during the dedication ceremony, viewable on pbs.org (https://www.pbs.org/video/honoring-dred-scott-1696964168/. “[The original tombstone] was so low that it was difficult to find. But it was still one of the top three gravesites at Calvary,” she said.

Scott takes his cause for freedom to court

Scott first brought his case to a Missouri state court in 1846, arguing that because he, his wife Harriet, and their two daughters, Eliza and Lizzie, had lived on free soil in both Illinois and Minnesota for several years, they had become free and should remain so, despite returning to Missouri, a slave state. After 11 years of victories and reversals in the court system, Scott’s appeal reached the Supreme Court.

On March 6, 1857, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney wrote for the majority in a 7-2 decision in the Dred Scott v. Sanford case, a ruling that went far beyond the issue of Scott’s right to freedom. It ruled that Blacks had no rights under the Constitution, fueling the debate over the future of slavery in the U.S. that historians say helped spur the country toward civil war. Taney, a slave owner himself, concluded that Blacks and their descendants were not protected by the Constitution and therefore could not be citizens, claiming that he had followed the Constitution’s “true intent and meaning when it was adopted.” He also wrote that as noncitizens, Blacks had no privileges granted by the Constitution and were not entitled to sue in court and said slaves were private property and thus should be treated as any other property and could not be seized without due process.

In summary, Taney’s opinion not only rejected Scott’s legal battle for freedom but relegated all Blacks to a permanent status of inferiority.

Scott granted victory in defeat

Ironically, the woman who owned the Scotts remarried during those many years of legal battling and her new husband was a congressman who opposed slavery. After the Supreme Court verdict in 1857, she transferred ownership of the Scotts to Taylor Blow – a son of the Virginia family who originally owned Dred Scott and supported the Scotts financially during their legal battles. Blow then emancipated the Scotts.

Scott had originally offered Eliza Sanford, the widow of his enslaver, $300 for his and his wife’s freedom but she refused, leading him to appeal to the court.

Sadly, Dred Scott lived just 16 months as a free man. On Sept. 17, 1858, he died of tuberculosis, leaving his widow to care for their two daughters.

“Dred Scott’s story started and ended here in St. Louis but a lot of what he did affected the entire nation,” Jackson said. “But his is just one of thousands of stories we need to acknowledge and understand. I wanted space on [his monument] to inscribe something for people to really see.

“Even though I knew what it was going to look like and put it all together, I still had tears in my eyes when it became a reality for all the world to see,” she added.