By D. Kevin McNeir

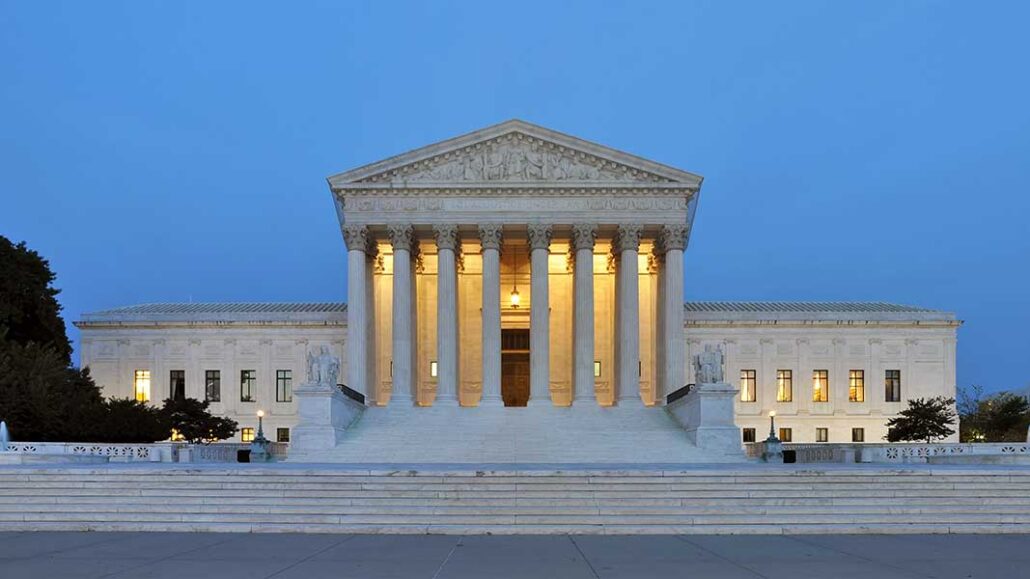

The Supreme Court justices, in striking down affirmative action in higher education and voting along ideological grounds – the conservatives members in the majority – recently determined that race-conscious admissions programs violate the Constitution’s guarantee of equal protection. In the words of Chief Justice John Roberts Jr., “the student must be treated based on his or her experiences as an individual – not on the basis of race.”

But for those who have not yielded to the alluring nature of baseless assertions that proliferate social media and “fake news” and are willing to take a realistic look at the current state of race relations in America, it’s difficult, if not impossible to give credence to the myth that we have successfully entered an era of “color-blindness.” In a scathing criticism of her conservative colleagues, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson delivered a profound history lesson in which she charted the policies and laws that have long supported racial discrimination and allowed for the deepening of inequality in the U.S.

“Gulf-sized race-based gaps exist with respect to the health, wealth, and well-being of American citizens,” she wrote in her dissent. “They were created in the distant past, but have indisputably been passed down to the present day through the generations.”

As she delivered an historical account of race relations in America, she continued to provide examples that revealed how African Americans have been, and continue to be treated as second-class citizens.

America may want the rest of the world to believe that as the exemplar of democracy, we are unequivocally invested in leveling the playing field and providing initiatives to counter centuries of educational and economic inequality that have directed been aimed at and impacted Black and Hispanic students, but the reality presents a far different picture.

The real deal remains that the ruling of the Supreme Court represents a seismic setback for students from marginalized communities, already struggling to overcome huge barriers in their efforts to take advantage of quality education in America.

As Crystal Sanders, an associate professor of African American studies at Emory University posited during an interview with an MSNBC columnist, “Without meaningful and concrete efforts to increase diversity in higher education, there will be fewer nonwhite physicians, attorneys, and teachers.”

Two members of the Court who both benefited from affirmative action policies, Justice Clarence Thomas (a Black man) and Justice Sonia Sotomayor (a Latina), provided distinctly different conclusions on the lessons they learned.

“Treating anyone differently based on skin color is oppression,” Thomas said, while Sotomayor said, “Ignoring racial inequality will not make it disappear.”

Lest we forget, white slaveholders barred enslaved Black people from learning how to read and write. During Reconstruction, white supremacists burned hundreds of Black schools to the ground while Jim Crow laws made sure that white schools were better funded than those with majority-Black student populations.

And while the successful effort led by Thurgood Marshall and his team of fellow attorneys in the Brown v. Board of Education case resulted in the Supreme Court ruling that “separate but equal” was unconstitutional, the backlash, which continues to this day, was swift and evocative.

What Thomas may want us to believe when he says that a “race neutral” standard serves as a viable antidote to affirmative action is anyone’s guess. As for this writer, even with grades and test scores that were in the highest percentile among my peers at University of Detroit High School – a Jesuit-founded, college preparatory high school on the city’s westside – matriculating at the University of Michigan in 1978 and graduating in 1982 was no walk in the park.

Blacks did not have old tests and notes from former students that we could utilize. Only a handful of Blacks could look to parents, siblings or other relatives who had graduated in previous years and could advise us at to which programs, professors and courses to take or to avoid.

Only through grit, determination, countless hours in the library, and with the support and encouragement of our own, mostly-Black study groups, were African American students able to claim their degrees.

Affirmative action may have allowed some of us to peek through the door where we could envision an entirely new future and unprecedented opportunities, but it did not give us a free pass. In fact, some of us are still awaiting permission to “pass go and to collect $200.”