By D. Kevin McNeir

Just over a year ago (April 2022), The Washington Informer, in a news report written in collaboration with Word in Black, an initiative of 10 of the nation’s leading Black publishers that frames narrative and fosters solutions for racial inequities in America, examined how D.C. Public School (DCPS) librarians were responding to the growing push for book bans across the U.S.

One librarian, as the reporter, Sam P.K. Collins noted, described the controversial issue of banning books from the perspective of her Ward 6 school – a perspective which stood in stark contrast to the experiences of her colleagues in more conservative strongholds like South Carolina and Louisiana.

“When you get into the business of telling a child they can’t read a particular book, you’re focusing on the negative and blocking them from accessing books that affirm their culture, race and identity,” said Boyd, who at the time of the interview had recently been chosen School Librarian of the Year.

“It hurts Black, brown and LBGTQ kids, more than their counterparts. School librarians have to be more on the political side and conscious about what’s going on in society,” said Boyd while adding, “book banning is a serious issue and censorship.”

For now, educators and elected officials in the District have not been swayed by the book banning banter. According to DCPS central office records, not one book was removed from the District’s public school libraries, pulled from the shelves, and restricted from classrooms due to content – at least through the end of 2022.

But in other parts of the country, things look markedly different. In just the first four months of 2022, Texas led the nation with 700 books banned, followed by Pennsylvania with 400 and Florida with nearly 300. Other states topping the list of banned books included Oklahoma, Kansas, and Indiana. Those numbers have remained on track for 2023, with Texas districts still at the top of the heap with the most instances of book bans at 438, followed by 357 bans in Florida, 315 bans in Missouri, and over 100 bans in both Utah and South Carolina.

In fact, the fury over and support of book banning has only escalated in 2023, dominating the discussions of and platforms for a growing number of political hopefuls, particularly Republicans – the majority of whom have used this divisive issue as a rallying cry in their quest for positions that range from local school board officials to the White House.

As we look to the 2024 presidential election, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis, given the laws he has already successfully pushed through the Florida legislature, has emerged as one of America’s most vocal advocates for book banning, claiming that he only wants to ensure that parents have control over their children’s education – a claim that has been refuted by Floridians and many Democrats as misleading, if not totally false.

Consider that in 2022, just over 3.8 items million items were checked out of the D.C. Public Library System, including 1,700 checkouts of top challenged books. The reasons for these challenges spanned from LGBTQ+ content to promoting an anti-police message, according to the American Library Association (ALA). And many of those challenged books were written by people of color, including Toni Morrison’s “The Bluest Eye” – checked out more than 600 times.

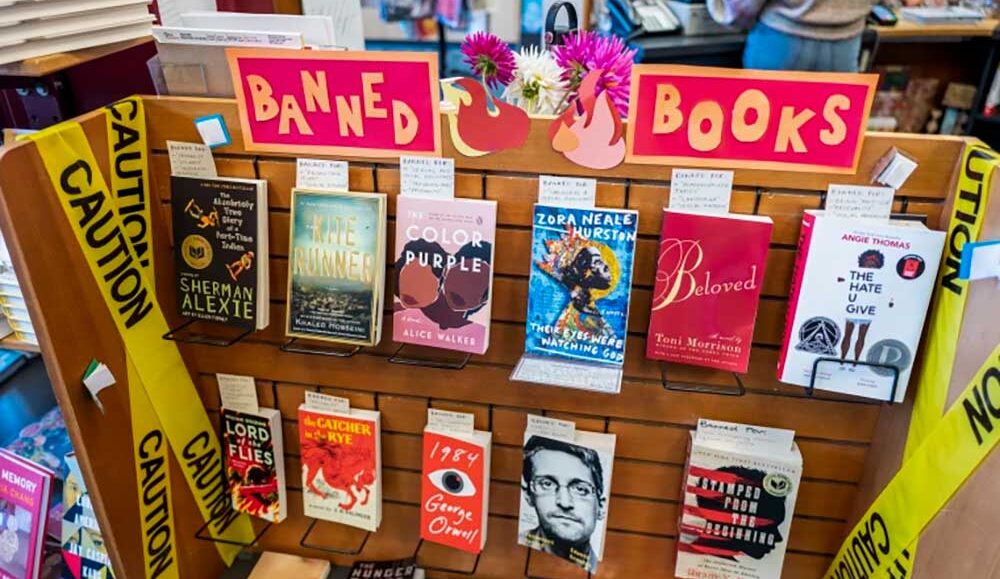

Can you imagine books like Isabel Wilkerson’s “Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents,” Toni Morrison’s “Beloved,” Maya Angelou’s “I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings,” George M. Johnson’s “All Boys Aren’t Blue,” or Nikole Hannah-Jones’s “The 1619 Project: A New Origin Story” – all books written by Black authors – being removed from classrooms and libraries because of their alleged “questionable content?”

Well, it’s happening. The question remains “where will it stop?”

More than 60 years ago, Ray Bradbury, in his acclaimed novel, “Fahrenheit 451,” imagined a bleak, dystopian future in which the job of a fireman was to destroy the most illegal of commodities, the printed book, along with the houses in which they were hidden.

In that world, ideas as presented in books and how they influenced society’s minds, were considered dangerous. Safety and national security rested in what people were told and taught, couched within the mindless chatter of television.

At the time of its publication in the 1950s, Bradbury’s prose was considered a science fiction masterpiece. However, it now seems that he may have been prophetic in his musings. Maybe he missed the mark in suggesting that television and the contents of its programs would become the “supreme educator.” But if one were to replace TV with today’s dominant forms of communication, the internet or social media . . . you get the point.

Banning books, while a hot topic today, is nothing new. It’s been around for centuries as those in power have attempted to legislate what should and should not be read. But in the past few years, there has been a disproportionate escalation of efforts to ban books by LGBTQ+ authors and authors of color whose stories address perspectives and touch on life which counter that of white, straight, middle-class Americans.

But the real losers may well be our children – youth who, if this firestorm continues, will be relegated to receiving a watered-down, sanitized version of history – a history that does not honestly or accurately reflect the many layers of today’s society.

A history that is HIS-story but not OURS.